The file is one of the most basic and essential tools found in the modeler’s

armamentarium. The proper file can rough out a shape rapidly or refine

and smooth the finest of details. Having a good selection of files will

enhance your creative potential. While files seem so common, they are

actually quite amazing tools. The first files were made completely by

hand with each tooth formed by striking a chisel at the proper angle and

interval. The first successful file cutting machines came into use in

the mid eighteenth century. This, along with improvements in the refining

of iron ore into steel and better heat treating processes, led to the development

of the modern files.

The basic parts of file are shown in Fig. 1. Files are sized by length.

American and Swiss files are measured differently.

Files are graded according to the degree of fineness or coarseness and

whether the teeth are single or double-cut, Fig. 2.

Single cut files have rows of teeth cut parallel to each other at an angle

of 65 degrees from the centerline. Sometimes referred to as “Saw Files,”

Single cut files are used for sharpening tools, finish-filing and draw-filing.

They are also the best tools for smoothing the edges of sheet metal.

Double-cut files have rows of teeth crisscrossed so the teeth become diamond-shaped.

The first row of teeth is called the overcut. On the top of these rows,

a second set of teeth is cut at a different angle to the file axis. This

row is known as the upcut and is finer than the overcut. Double-cut files

are generally used for rough work and fast removal of material. They are

sometimes referred to as "Machinists’ Files".

Curved-cut is an arrangement of file teeth in curved contours across the

working face of the file. The teeth are milled with a decided undercut

(or positive rake). These files are used mainly for automobile body repair.

Rasp-cut is a pattern by which each tooth is formed individually by a

single-pointed tool or punch. These files are generally used for wood.

Some files have edges that are uncut or smooth. This edge is often

referred to as a “safe edge.” These files are extremely useful for highly

precise detail work, Fig. 3.

The fineness or coarseness of a file indicates the spacing of the teeth

and the number of teeth per inch, Fig. 4. There are four different grades

for American Pattern Files: Coarse Cut, Bastard Cut, Second Cut, and Smooth

Cut. They range in that order from fewest to most teeth per inch. The

differences from Coarse to Smooth are relative to the length of the file

because coarseness of a file increases as the length from point to heel

increases. In other words, a 6” file, either single or double-cut, has

more teeth per inch than a 12-inch file.

Swiss pattern files are graded from 00 – 6, with 6 being the finest.

They are commonly sold in sets of grades 2, 4, and 6. Swiss pattern files

are always double-cut.

It is easier to learn how to operate a lathe than it is to learn the techniques

of proper filing. The ability to achieve precision with a file is an art

and the mark of a true craftsman. In the old days, an apprentice would

be given exercises that would require him to file a perfect cube or file

two pieces that were to fit together perfectly. The only way to master

these techniques is to practice.

There are three basic filing operations:

Straight-forward filing: in which the file is pushed straight ahead

across the work. The teeth of the file only cut in the forward stroke.

The file should be carried forward in an almost straight line with the

pressure first applied on the tip in the beginning of the stroke; on the

tip and heel while in the middle of the stroke; and finally on the heel

at the end of the stroke.

If pressure is applied on the return stroke, the teeth are dulled and

the file can be quickly ruined. Except when working with soft materials,

the return stroke should be made with the file lifted clear of the material.

If too much pressure is used on the forward stroke, the teeth are liable

to clog or even shell off (the breaking of teeth caused by excess pressure,

back raking, or filing sharp edges or corners).

A typical beginner fault is rocking the file or trying to remove too much

material at one time. Both actions usually produce a convex surface.

Make sure the file is clean before starting. The file can be easily cleaned

with a file card, Fig 5. One trick is to rub chalk into the teeth of a

new file to prevent the teeth from clogging. Chalking also helps to prevent

pinning (tiny particles of fillings that wedge between the teeth) that

can scratch the work.

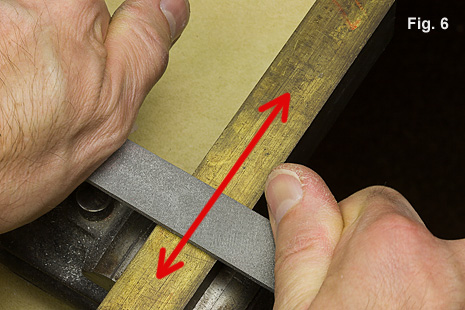

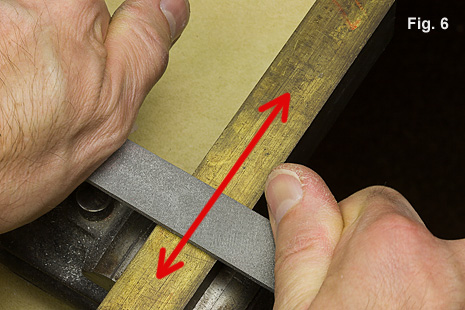

Draw-filing: in which the file is grasped at each end and with

an even pressure, alternately pulling and pushing over the work. The file

is held perpendicular to the direction of motion, Fig. 6. One advantage

of draw-filing is that the file can be held steadily. As a result, a fine

surface finish can be obtained. Draw filing is usually done with a single-cut

mill bastard file or a long-angled lathe file so that the metal is cut

with a true shearing action that avoids scoring. In draw-filing it is

important to balance the pressure over the entire stroke so that a hollow

spot does not develop in the center.

Lathe-filing: in which the file is stroked against the work that is revolving

in the lathe, Figs. 7, 8. Lathe filing is used to smooth out small flaws

from the cutting tool, create a free form shape, or make small corrections.

With the work turning toward you, hold the file at a slight angle and use

a long forward stroke, moving laterally about half the width of the file.

Do not hold the file rigidly or stationary, but keep continually stroking.

Clean the file frequently as it will clog quickly.

Take care of your files. New files should be broken in on flat surfaces

of soft metals. Use only light pressure. Don’t just throw your files

in a drawer. Care should be taken to keep each file separate. Keep them

in a rack or drawer with partitions, Fig. 9, 10. Be sure to keep files

away from water or moisture and avoid getting them oily. Oil makes the

file slide across the work surface without cutting. Get in a habit of

cleaning your files with a file card before putting them away. With care,

a quality file will last a long time.

Here is a chart of the more common file shapes.

Flat: Considered the “work horse” of files. In a full size file

it tapers in width and cuts on all sides. As a Swiss pattern file it is

more commonly found to be parallel in width and thickness with one edge

safe (uncut).

Equaling: Used for slots, corners, and narrow openings. Equaling Files

are double cut on the sides, single cut on the edges, and are parallel

in width and thickness.

Checkering: Are parallel in width and gently tapered in thickness. They

have teeth cut in a precise grid pattern: Over cut is parallel to file

edges and under cut is 90 degree to over cut. Checkering files are used

for putting serrations on knife edges and to obtain a checkered design

similar to a gun handgrip.

Pillar and Pillar Narrow: Used for precision work or to finish

work begun with a Hand File. Pillar Files are double cut on both

sides, safe (uncut) on the edges, and are parallel in width and taper in

thickness.

Square: A general purpose file also used in corners and holes. Square

Files are double cut on all sides and taper toward the point in width and

thickness.

Three Square: The triangular shape is excellent for use in corners and

on dies. Three Square Files are double cut on the sides, single cut on

the edges and taper toward the point in width and thickness. Despite having

angles of 60 degrees rather than 90 degrees, these files are still referred

to as Three Square simply as a matter of slang.

Barrette: For cleaning gear teeth, keyways, dovetail ways, and sharp

angled slot ways. Barrette Files are double cut on the flat side, safe

(uncut) on the beveled back side, and taper toward the point in width and

thickness.

Crochet: Ideal for filing joints between flat and curved surfaces or

developing slots with rounded edges. Crochet Files are double cut on the

sides and edges and taper toward the point in width and thickness.

Veneer Knife: Similar to Crochet file, but are uniform in thickness

and width.

Round Edge Joint: Are parallel in width and thickness, with rounded

edges. The flats are safe (uncut) and cut on the rounded edges only.

Used for making joints and hinges.

Warding: Ideal for filing slots and removal of burrs after milling

operations. Warding Files are double cut on the sides, single cut on the

edges and taper toward the point in width.

Half Round: Great for curved surfaces and corners. Half Round

Files are double cut on both sides and taper toward the point in width

and thickness. Ring Files are narrower than a standard half

round and taper in width and thickness, coming to a point. Used for filing

inside of rings.

Marking: Similar to half round except flat side is safe (uncut).

Crossing: Excellent for filing interior or curved surfaces. The double

radius makes possible filing at the junction of two curved surfaces or

a straight and curved surface. Crossing Files have two "half round" sides

with one side "flatter" than the other and are double cut tapering

toward the point in width and thickness.

Round Straight: Round

Straight Files are double cut and are parallel in width and thickness.

Round Taper: Round

Taper Files are double cut and taper toward the point in width and thickness.

Pippin: Combines the cross sections of Round and Crossing Files with

the edge of a Knife File and is excellent for finishing junctions or opening

slots with a "V" shape. Pippin Files are double cut and taper

toward the point in width and thickness. (Pippin Files are often referred

to as "Apple Seed" files.)

Knife: Wedge section shape is great for working in slots. Knife Files

are double cut on the sides, single cut on the "knife edge," safe

(uncut) on the back, and taper toward the point in width and thickness.

The knife edge usually has an arc to it.

Slitting: For acute angle filing and where a Knife File will not fit.

Slitting Files are double cut on all four sides, single cut on the edges,

and are parallel in width and thickness.

Slotting: Narrower than slitting file with flat uncut center portion.

Used for creating slots in screw heads